I’m about to turn 36. Most friends my age are either drowning with mortgage payments or aggressively saving for a deposit. I’m in the very fortunate position of having enough for a deposit for a place far bigger than I need as a single person, and supportive parents who would be only too happy to help if I needed an extra hand getting into the property market.

There’s only 1 problem: I don’t want to. That makes me something of an aberration in Australia. I can certainly see the benefits - rent has gone through the roof in recent years, and I won’t pretend I enjoy dealing with real estate agents. But home ownership comes with its own set of downsides, from mortgage stress, maintenance costs, and general immobility. I like the idea of being free to move interstate if I need to change jobs, or up-sizing if I find the right person and want to start a family without paying transaction costs, or going on holiday between leases if I decide to move. I understand the Australian dream of owning one’s own home - it’s just not my dream right now.

While some people I talk to can appreciate that perspective, the overwhelming consensus is that rent money is dead money, and that I’m compromising my financial future. I know it’s blasphemous to say so in Australia, but that simply isn’t true.

Recently there have been a host of articles discussing the wealth divide between owners and renters amongst retirees. While this wealth divide no doubt exists, the conclusions these articles draw are absolutely preposterous, and the solutions they propose will only exacerbate the problem.

As with all things I write, this is not financial advice. I’m not a financial adviser - just a guy on the internet who isn’t afraid of numbers. Check out the code if you want to see how the plots below were generated or run your own simulations.

Lamborghini Owners are Better Off In Retirement

I don’t have a survey to back up this claim, but I’m going to go out on a limb here and guess that the subset of retirees who own at least one Lamborghini has a higher average net worth than those that don’t. Logically then, we should be doing everything we can to ensure every young person can own a luxury car, and subsidize their loans to ensure they can make the purchase as early as possible.

Hopefully the logical fallacy in the above is obvious. In the context of luxury cars, the implication that ownership generates wealth is transparently backwards. In the context of home ownership though, nobody bats an eyelid, and the solutions people suggest are nothing short of infuriating.

The most egregious of these, in my opinion, is this case study, because

- they actually do a quantitative analysis with simple figures;

- the authors disparage the superannuation system despite failing to use it effectively;

- the authors are retirement planners/actuaries who should know better; and

- it’s posted on the Actuaries Institute website, an organization who should have the technical knowledge to identify the blatantly unfair comparisons and demonstrably wrong conclusions (there is a generic disclaimer distancing the organization from the opinions of the authors, though I would argue propagating others’ arguments implies at least a degree of support and provides credibility).

The Pro-Ownership Argument

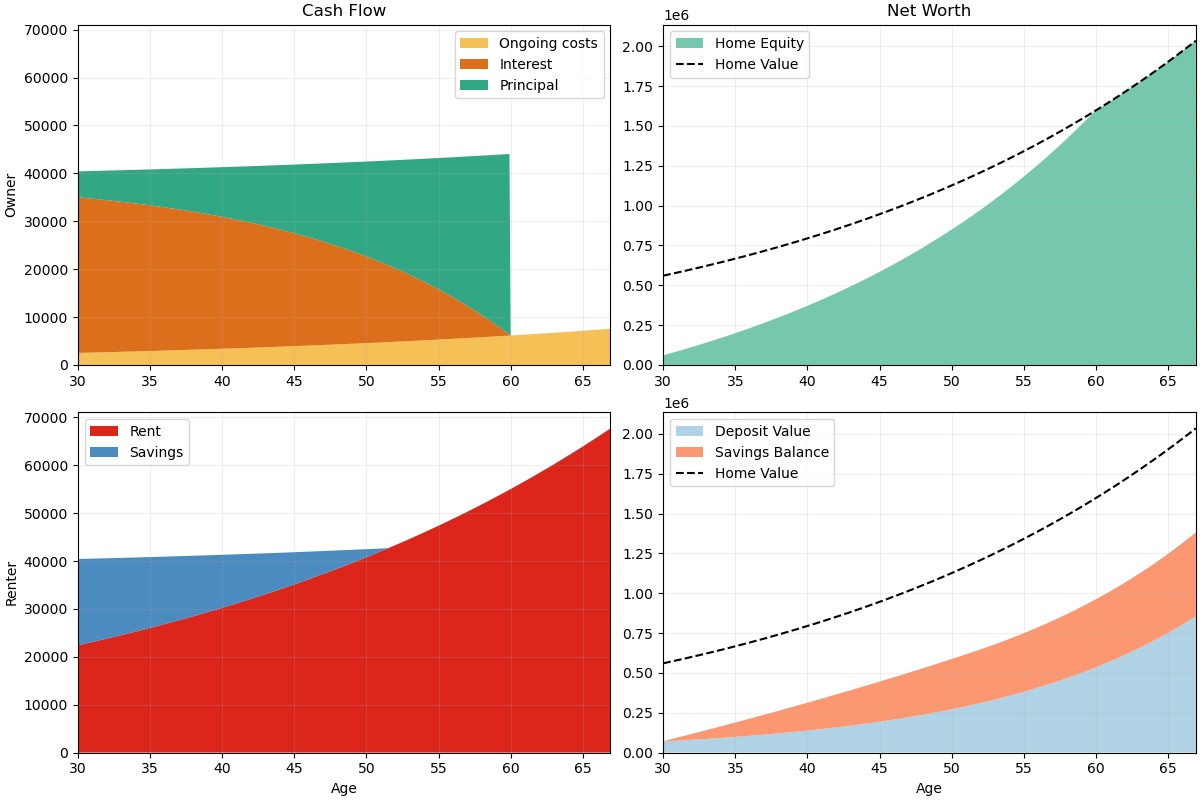

The case study compares a 30-year-old couple’s financial performance using two investment strategies. In one case they purchase an apartment, pay off the mortgage at a constant rate, and then live rent free; the other where they rent the same apartment with increasing rent each year, putting their deposit into superannuation and saving the initial difference between their rent and what they would be paying as a mortgage. Specifically,

In the home owner case:

- the home has a purchase price of $560,000;

- there’s a $10,000 acquisition cost

- after the acquisition cost has been paid, $60,000 is left for a deposit;

- they get a 30 year bank loan for the outstanding $500,000 at 6.5% p.a.;

- the property appreciates in value at 3.5% p.a.; and

- maintenance, insurance, council rates, and other ongoing costs total to $2,500 in the first year, increasing by 3% p.a..

In the renting case:

- the couple make a $70,000 non-concessional contribution to their superannuation;

- after fees and taxes, their superannuation appreciates at 6.8% p.a.;

- annual rent is $22,400 (4% initially), increasing by 3% p.a.;

- they save the difference between what they would otherwise be paying in the owning case and the rent while it’s positive, and continue to pay rent after it exceeds the mortgage repayments even once the mortgage has been paid off in full; and

- those savings appreciate at 3% p.a. after taxes are paid.

In each case they ignore compulsory superannuation contributions.

Below are the resulting cash flows and net worth over time.

Cashflow and net worth over time

Despite the lower payments from about aged 50 - and significantly lower payments after the mortgage is paid off at 60 - the home owner comes out far ahead, with a $653,000 higher net worth - almost 50%.

They conclude that home ownership leads to a better financial outcome than renting. They attribute this to leverage:

The main driver of this is the fact that homeowners benefit from the growth of an asset that’s up to 10 times larger than the deposit they invest.

They thus argue that compulsory superannuation is cruel since it diverts income away from savings for a deposit:

Current policies that force young workers to… divert 12% of their salary to superannuation (from 1 July 2025) are almost cruel - especially when young people desperately need that money for a home deposit.

What If We Consider a Renter Who Isn’t Financially Illiterate?

Growing equity in a home is undoubtedly one vehicle for saving for retirement. The authors use this case study to imply that it’s a better vehicle compared to superannuation. The problem with this is that in their analysis, they don’t compare home ownership against effective use of superannuation. They have the renter use a savings account yielding 3% p.a. after tax. Most of you reading will know this is a terrible retirement strategy. You’d be hard pressed to find a 30-year-old who doesn’t know this. The authors of this case study definitely know this, yet they still suggest it’s appropriate in a “like-for-like” comparison. Absolute hogwash.

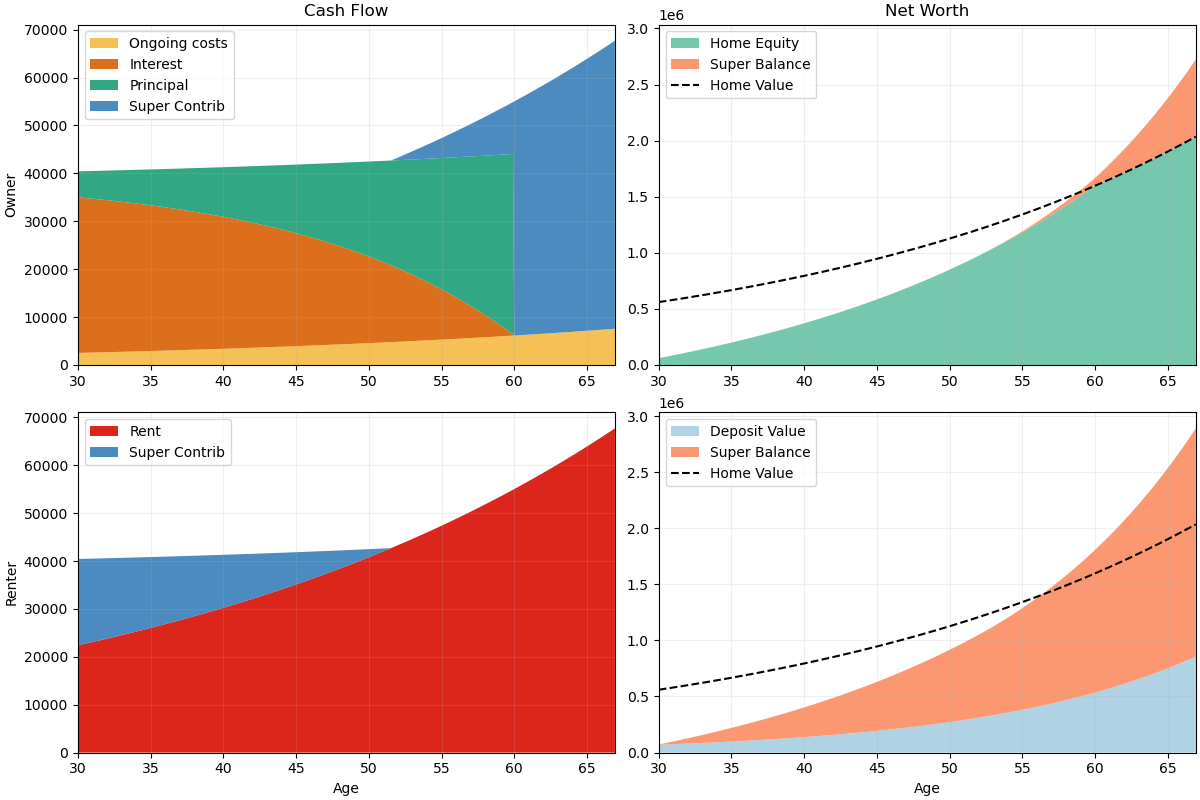

What happens if we change those savings into concessional superannuation contributions? We’ll assume our renters are in the 30% tax bracket. This means that every $1 of after-tax income they contribute, their super will receive $1 * (1 - 15%) / (1 - 30%) = $1.21, and that investment will appreciate at 6.8% p.a. rather than 3% p.a..

To even things up, we’ll also make our home owner contribute the difference between rent and their mortgage in the later time period as concessional contributions. This makes the total cashflow plots look a little odd in isolation, but it ensures in both cases they’re outlaying the same amount of money. If you’re a visual person, we’re defining the blue area (super contributions) in the cash flow plots such that the silhouettes are the same.

It would also lead to a better outcome for our renter if we assumed that the $70,000 the couple starts with was made up of concessional contributions (i.e. 21% bigger), but we could also argue that for the home owner case (assuming they made it over a number of years, they could access it with the FHSS scheme). This would have more complicated tax implications though, so we’ll ignore this in both cases to keep things fair and simple.

Cashflow and net worth over time when savings are contributed to superannuation

Cashflow and net worth over time when savings are contributed to superannuation

Surprise surprise, our renter now comes out ahead by about 6%, or $167,000. If our couple wants to buy the apartment at retirement they can now do so by pulling a lump sum out of their super and still end up ahead compared to if they had bought at the beginning of the period.

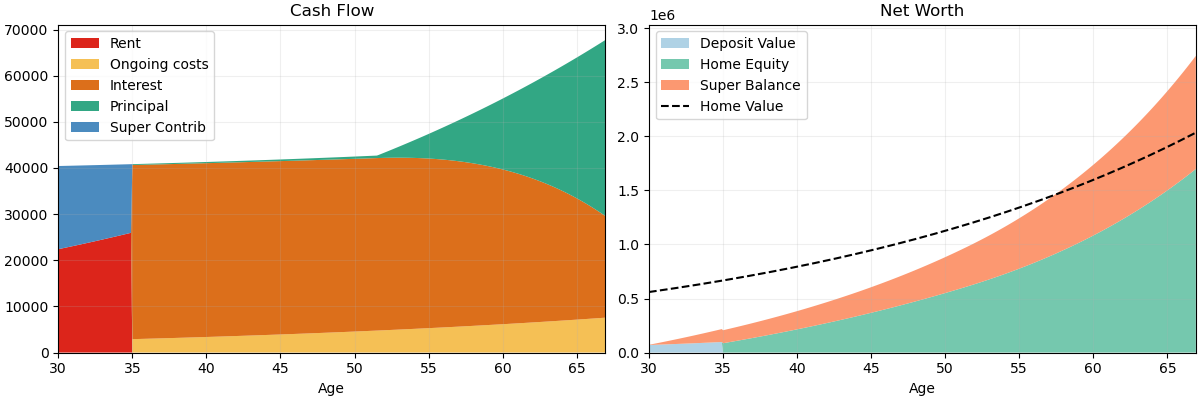

What happens if our couple doesn’t want to wait until retirement to own though? Well, they can always do a hybrid approach. Thanks to the FHSS scheme, they can still access the initial $70,000 plus earnings (in practice they could access at least $30,000 more if they pooled their allowance, plus any gains on that since contributing - but we’ll ignore that for simplicity). We assume acquisition costs grow inline with property value (i.e. 3.5% p.a.). Below is the result if they buy their apartment after 5 years.

Cash flow and net worth buying after 5 years

In this case, they can only just afford the interest payments at time of purchase, though once they start increasing their total cash flow they do begin to work down the principle. Despite spending over 15 years barely paying off the loan though, those 5 years of additional super contributions at the beginning mean they end the simulation with almost exactly the same net worth.

In reality, they might have trouble getting a bank loan under these terms, though they’d also be able to access more of their super for the deposit via the FHSS scheme. Pulling that money out would lead to a slightly lower retirement net worth, since it’s return of 6.8% p.a. is higher than the loans 6.5% p.a. interest rate, but this difference isn’t enough to make a qualitative difference to the outcome.

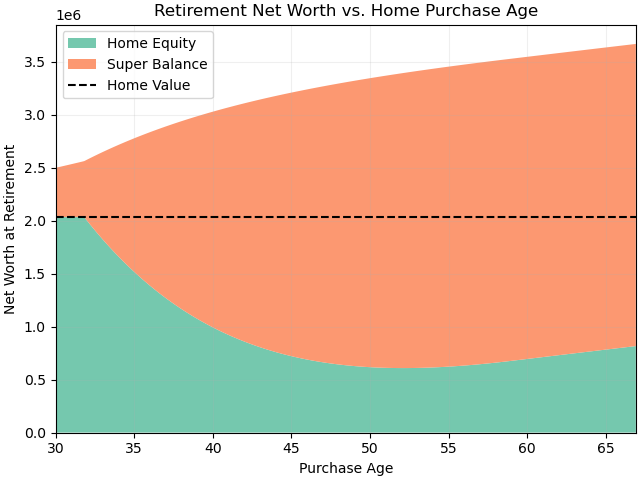

Retirement net worth vs purchase age

If we repeat the above analysis for every possible purchase age and look at the final net worth, we see that while the age at which our couple purchases the property affects the composition of their net worth at retirement, the total amount remains almost constant.

If we look at the assumptions, this shouldn’t come as a surprise. Initially, the home yields a net 7.05% p.a. return (3.5% capital gain + 4% imputed rent - 0.45% ongoing costs), diminishing to 6.47% p.a. (3.5% capital gain + 3.34% imputed rent - 0.37% ongoing) at retirement. This is pretty close to the 6.5% p.a. interest rate they’re paying, so the benefit of leverage is small. It’s comparable to the 6.8% p.a. they receive from superannuation contributions, but they don’t get the 21% boost to concessional contributions from the tax break.

About Those Other Assumptions Though

I would just like to stress that the above says nothing about the validity of the assumed returns in the original case study, and the final outcome is very sensitive to these. For example, some cursory googling suggests the initial 0.45% p.a. figure (that decreases over time) for ongoing costs (insurance, rates, body corporate, maintenance, council rates etc.) looks awfully optimistic. If we fix that to, say, 1% of the apartment cost, retirement net worth monotonically increases with purchase age - i.e. you’re always better off buying later. Renting for life leaves you with an extra $1.2 million at retirement, or a 48% higher net worth.

Retirement net worth with 1% p.a. maintenance cost

Similarly, the 6.8% expected superannuation returns after taxes and fees looks on the low side to me. My super account has returned 10.3% per year over the last 10 years after fees and taxes, and I’m fairly sure a self-managed super fund with diversified ETFs could achieve similar returns with a lower fee. Even if we only increase the super returns slightly - say, to 8% p.a. net of fees/taxes - and keep the same maintenance cost structure as above, our renter ends up with $3 million MORE than our owner - over double the net worth.

Having said that, if one wanted to make the home owner case stronger one might argue the interest rate is too high or the capital appreciation rate is too low. If we reduce the interest rate by from 6.5% p.a.to 5.5% p.a. and increase the capital appreciation rate from 3.5% p.a. to 4.5% p.a., our renter still ends up almost 40% ahead (still using an 8% p.a. net super return and 1% p.a. fixed maintenance rate).

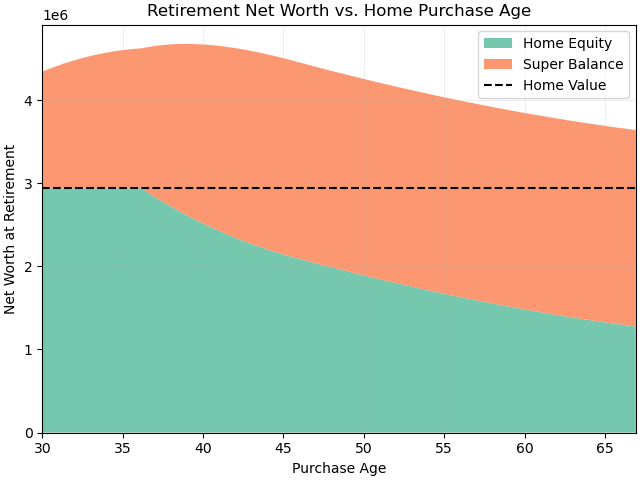

One last case I’ll identify is if we make all of the above changes and also make rent scale with property value (i.e. grow at 4.5% rather than 3%). Our retirement net worth is given below.

Retirement net worth with 1% p.a. maintenance cost, 8% p.a. superannuation returns, 5.5% p.a. interest, 4.5% p.a. fixed rental yield, 4.5% p.a. capital return

Now whether you think these assumptions are realistic or not, you have to admit the results are interesting. The property has a fixed net return of 7.5% p.a. (4.5% capital + 4% rent - 1% maintenance) which is slightly less than the 8% p.a. superannuation return, but significantly more than the 5.5% p.a. interest rate, so leverage plays a bigger role. Buying a home in this context is beneficial to renting forever, but delaying purchase for about 10 years is better than immediate purchase.

I’m not saying this last example is the most valid - with rent increasing faster than wages it’s safe to say the assumptions are at least unsustainable. Rather, my point is to highlight the counter-intuitive dynamics at play and the sensitivity of outcomes to parameter choices. It is certainly not the case that “buy now” or “rent forever” is the optimal policy for every configuration, and there are many worlds where optimal behaviour lies somewhere in the middle.

So Buying a Home is Bad For Wealth Accumulation?

Let’s assume we we are absolutely certain we live in the base-case with high maintenance world outlined above, where net worth monotonically increases with purchase age.

The analysis above assumes that all contributions to superannuation are concessional. If you hit the $30,000 per person annual concessional limit (which includes employer-paid compulsory contributions) - or those contributions drop you down into the 16% tax bracket - then further contributions would receive less favourable tax treatment. For example, re-running the fair base case (original low maintenance costs but savings contributed to super - 2nd plot above) without this favourable tax treatment means early home purchase is slightly advantageous - though only by about 3%.

This suggests that if you want an optimal retirement outcome then you should purchase a home when you can afford the repayments on top of maxing out concessional contributions. That said, anyone who can max out their concessional contributions for 37 years while also affording a mortgage is likely to be fine in retirement either way.

This analysis also makes no attempt to model investment property returns, which have different tax implications (tax deductible interest and ongoing costs, but tax-liable rent and capital gains), nor does it factor in volatility.

I’ll also point out that just because housing is arguable a bad vehicle for saving for retirement doesn’t mean it’s a poor investment in retirement. Owning your own home removes the volatility of rent from your expenses, and reducing volatility is generally desirable for retirement. Your principle residence is also exempt from the aged pension asset test, so as far as I’m aware there’s nothing stopping you draining a multi-million dollar lump sum from your super, purchasing some prime real estate the having your other living costs paid for by the government. You can probably guess my thoughts on that particular policy, but that’s a discussion for another time.

Why The Wealth Gap Then?

To be clear, I’m not disputing that amongst today’s retirees there is an enormous wealth gap between those that own a home and those that don’t. Most recent articles quote a recent HILDA survey that gives convincing statistics supporting this. Why does this gap exist if housing isn’t inherently a good savings vehicle? I can think of 3 reasons.

- Australia has seen an unprecedented housing boom over the last 30 years, thanks largely to generous tax concessions and interest rates that, until recently, have been almost monotonically decreasing. The fact that housing has resulted in so much appreciated wealth is the very reason we shouldn’t expect it to continue. The housing crisis in Australia is already at breaking point, with rent for a median home currently at 40% of the median household’s after-tax income. That’s not a mortgage - just rent. This article does a better job than I can of demonstrating what’s required to bring things back to a non-crisis levels, and it’s not pretty for the long term home owner. Past performance is not indicative of future returns though, and I don’t believe much more can be squeezed out the market;

- optimal or not, most people prioritize purchasing houses over saving for retirement; and probably most importantly

- a suboptimal retirement savings vehicle is better than no retirement savings vehicle (or even a savings account yielding 3% returns).

If you don’t invest for retirement, you will be poor in retirement. This should come as no surprise. Housing is one possible investment, but there is little evidence it will be optimal moving forwards.

Back to the Media

Now maybe you think I’m over-reacting to what is, after all, a single article. It’s not just one though.

This article by Ken Raiss, the director of a wealth advisory titled “Why Home Ownership Still Matters More Than Super” has so many conclusions I have issue with that it’s hard to quote them all without just copying the entire article. Some highlights include:

Owning your home is still the cornerstone of wealth creation. While superannuation is important, property continues to play the dominant role in financial security.

The earlier you enter the property market, the better. Rising prices mean younger generations need a strategy to get in sooner rather than later.

With declining home ownership rates among younger Australians, more people could find themselves spending their entire lives renting – and then retiring without the safety net of housing wealth.

The implications are huge:

- Greater reliance on government support like the age pension.

- Increased financial stress on older Australians.

- A two-tiered retirement system - one for those who own property, and another for those who don’t.

Now maybe Ken’s operating on different assumptions to those in the analysis above - but if not, I hope it’s apparent how harmful believing these points could be. Housing wealth may well continue to dominate superannuation in retirement, but it will do so because of scaremongering and incorrect interpretation of statistics like these - a self-fulfilling prophecy that will leave the poor resigned to poverty and the wealthy worse off.

Michael Read writes in the Australian Financial Review that

The average home-owning retiree is now worth almost $1.7 million – six times more than a retired renter – according to a new report warning that superannuation alone will not be enough to spare more Australians from a financially precarious retirement.

Maybe superannuation won’t be enough because nobody contributes to their super until after they’ve paid off their mortgage, Michael. Superannuation alone is precisely what could spare Australians from a financially precarious retirement, especially if they’re struggling to afford a mortgage - they just need financial education rather your blatant fear-mongering.

Our national broadcaster ran a story about a 66 year old civil servant who was delaying retirement to pay down her mortgage. No Linda! Put it into your super! Get the tax break and pull it out as soon as you retire to pay down the mortgage!

While it’s a little more dated, this article from The Conversation and later shared by the Grattan Institute has a whole section titled “You’ll be OK if you own”. While the data support that, it seems at best misleading to not also mention you may be better off if you choose not to.

I could go on. All these articles relate later entry into the housing market to poorer retirement outcomes. At no point in any of them does anyone even hint that maybe - just maybe - the causal factor might be the amount invested into wealth appreciating assets rather than the particular choice of assets, or that the solution to retirement funding might be to use Australia’s system designed specifically for retirement funding.

Conclusions

There are many benefits to home ownership - including, potentially, as an investment in retirement. That doesn’t mean it’s a good vehicle for generating wealth for retirement. In the past, decreasing interest rates and high capital returns made real estate an enormous wealth generator, but those factors were never sustainable. Australia’s superannuation system is designed specifically for saving for retirement and is, surprisingly enough, a particularly good vehicle for saving for retirement.

If you’re poor you’ll likely rent forever - but renting forever won’t make you poor.